Markets

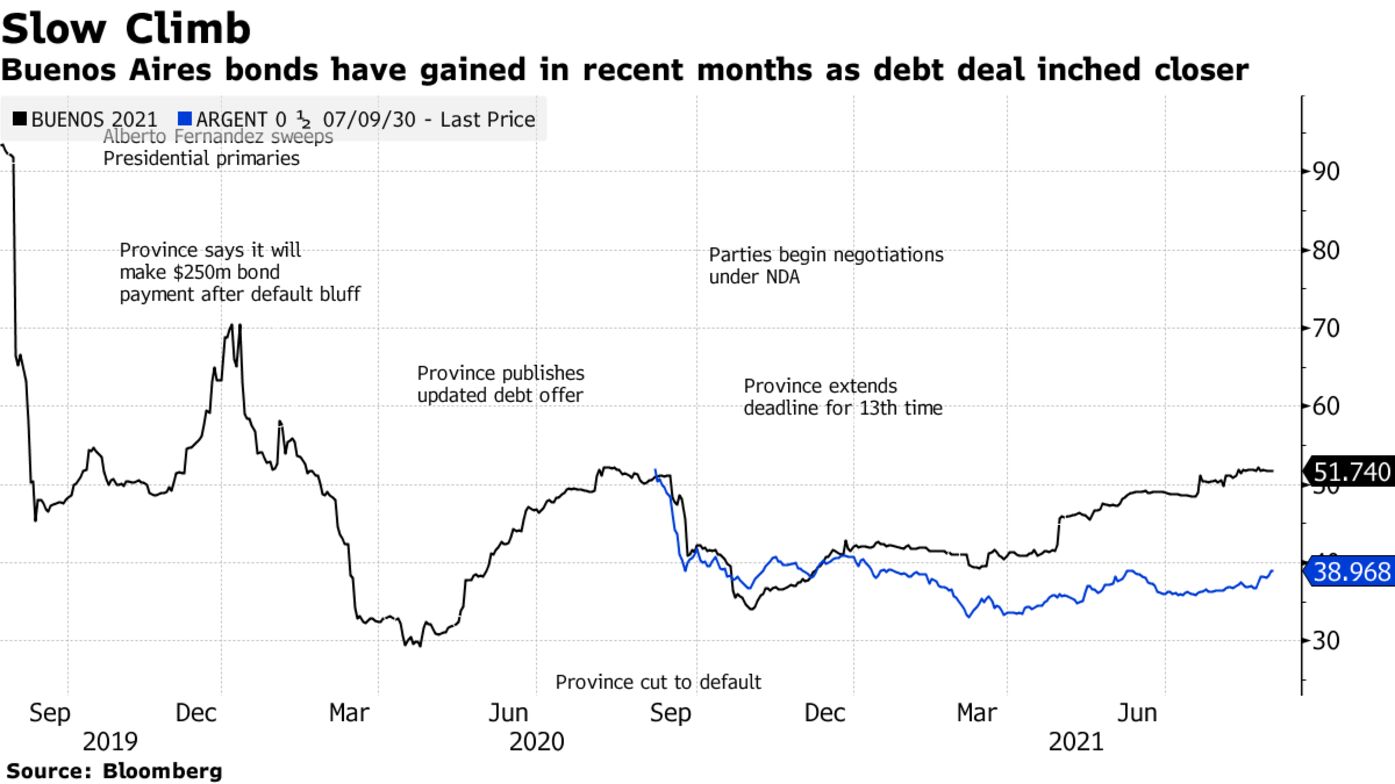

Buenos Aires Scares Creditors Into Accepting Bond Swap

By- Province got an accord for $7.1 billion in defaulted bonds

- Governor reviled by investors succeeds with ‘coercive’ deal

Axel Kicillof, the outspoken governor of Buenos Aires, called journalists to one of the province’s opulent 19th-century mansions and conceded defeat.

It was early 2020, just weeks before the pandemic hit, and Kicillof, a man reviled in investing circles for his brash negotiating style when he was economy minister during Argentina’s default a decade ago, was once again doing battle with creditors. This time around, he lamented bondholders’ “enormous intransigence” in refusing his province’s request to delay a $250 million bond payment.

He eventually coughed up that money for investors, but now it seems like the 49-year-old governor may have gotten retribution.

The province announced Monday it managed to cram through a restructuring for almost all its $7.1 billion of defaulted debt, swapping it for new securities valued at just over 50 cents on the dollar. Some creditors are grumbling that Argentina’s wealthiest province could have done better, but say in practical terms they had no other choice than to accept the deal.

That’s because the offer was structured in such a way that investors either needed to vote in favor of it, or risk getting dragged along at much worse terms. Their ability to fight was also hampered by the province’s plan to use complex legal tactics that would make it easier to compel reluctant creditors to take part in the deal, a strategy that also irked investors during Argentina’s sovereign debt restructuring last year.

“This was essentially a gun-to-the-head tender, where the province used extreme levels of coercion to achieve creditor acceptance,” said Richard Deitz, founder of London-based VR Advisory Services and a member of the creditor group’s steering committee during the negotiations. “That may get your deal done, but it’s not going to endear you to creditors in the long term.”

At the heart of the issue are terms written into the province’s bonds’ called collective action clauses, which stipulate what percentage of holders need to accept a deal to also bring along creditors who voted against it. They’re designed to avoid a situation in which an overwhelming majority of investors agree to a deal, but a few holdouts stand pat and demand full repayment.

To complete the deal, Buenos Aires used a controversial strategy called “re-designation” to leave portions of two bonds out of the restructuring, allowing the rest of them to go through. Used in both Ecuador and Argentina’s debt workouts last year, re-designation is intended to help restructurings cross the finish line when a deal’s success is threatened by just a few small series of bonds.

“The province’s offer didn’t seem designed to persuade people to enter a quick and consensual debt exchange,” said Mitu Gulati, a law professor at University of Virginia who writes about sovereign debt contract law. “Rather, it seemed to be testing the boundaries of the legal limits of collective action clauses.”

The economic terms of the deal were also punitive for creditors who voted against the accord but ended up getting dragged into it anyway. Under the structure created by the province, those investors will get bonds with lower interest rates that get paid out in Argentina, where capital controls make getting dollars out of the country onerous. Holdouts will also forfeit their share of almost $800 million in interest accrued by the province while it sat in default.

Funds that objected to the deal, including VR Advisory Services, said the province, its lawyers and its largest creditor, GoldenTree Asset Management disregarded their input. But the deal’s terms were so effective at dissuading holdouts that those funds ended up voting in favor of the accord anyway, since they didn’t hold enough of the province’s bonds to block the exchange.

A spokesman for the province said the economic and legal terms of the deal were reached by mutual agreement with bondholders to encourage majority participation. Kicillof called the accord “mutually convenient” at a press conference Monday.

Buenos Aires said that it got support to restructure 98% of its overseas debt, with the exceptions being portions of a $250 million note due in 2021 and a 95 million euro bond due 2020, which had been issued under rules that required a higher amount of creditor participation to pull all holders along. Economy Minister Pablo Lopez didn’t specify what percentage of those bonds were left out of the deal, and it wasn’t clear who the holdouts were or what their strategy was for getting paid back. Lopez said he intended to work with creditors on finding a solution.

The new securities could trade as high as 80 cents on the dollar as Argentina’s economy recovers from last year’s pandemic-induced contraction, and as the federal government renegotiates a $45 billion lending program with the International Monetary Fund, according to Hans Humes, a portfolio manager at Greylock Capital Management, which was involved in the negotiations.

Given the fairly positive outlook for the credit, Buenos Aires might not have needed to be so aggressive in its approach, and bondholders also had a right to be angry about Kicillof’s strategy, according to Siobhan Morden, the director of Latin American fixed income at Amherst Pierpont. She said the notes effectively trade at a discount because of their ties to Kicillof.

“It seemed unnecessary to shift towards coercive tactics when the actual terms were quite friendly,” Morden wrote in a note. “But bondholders have a responsibility to defend the international financial infrastructure, especially against serial defaulters that set precedent with coercive tactics.”

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen