‘Dead cow’ awakens as pipelines revive shale hopes

In a windswept desert southwest of Buenos Aires, black steel tubes the length of school buses extend in a line toward the horizon. The scene is the clearest sign yet that one of the world’s biggest shale plays finally has a shot at living up to its promise.

Workers in the geological formation known as Vaca Muerta — Spanish for “dead cow” — are building a 356-mile (573-kilometre) pipeline that will carry natural gas from remote northern Patagonia to Argentina’s cities and industry centres in the east. The project, along with the planned expansion of an oil conduit in the same area, will help relieve bottlenecks that have stifled production of fossil fuels the nation desperately needs to bolster its economy.

While Argentina’s energy industry has seen its fair share of false dawns in recent years, construction of the pipeline is an irrefutable step toward a much-cherished goal of cutting the country's dependency on fuel imports — and perhaps even regaining the status it held 20 years ago as a key energy exporter.

The progress in Vaca Muerta comes as the US shale boom slows, the war in Ukraine roils the global gas market and the world’s centres of oil-production growth shift to South America, including Guyana and Brazil. It’s also happening in spite of government restrictions on crude prices and money flows.

“The critical steps are being taken — there’ll be no piece of infrastructure missing to sustain Vaca Muerta growth in the near-to-medium term,” said Marcelo de Assis, an oil and gas researcher for Wood Mackenzie in Rio de Janeiro. “But there are still above-ground risks. Price caps are a policy for election cycles, yet drillers need long-term stability, and capital controls are a killer.”

First major duct in decades

In Vaca Muerta one morning late last year, workers soldered giant steel pipes and excavated chunks of sandy earth, carving out the cross-country route that the pipeline — named President Néstor Kirchner, after the former leader — will take. By many accounts, it’s Argentina’s first major gas duct in decades.

The pipeline is, in large part, a product of Argentina’s current government led by Alberto Fernández. The president, whose term ends this year, also fixed oil prices far above market levels in 2020 to avoid decimating Vaca Muerta production during the pandemic-driven price crash. While the previous administration, led by pro-market Mauricio Macri, helped reduce the country’s reliance on gas imports, renewable energy was the bigger focus.

The conduit’s developer, state-owned Energía Argentina SA, plans to have it ready by June 20, a national independence holiday. Coincidence or not, the duct’s start-up promises to be a victory lap of sorts after years of setbacks, including the pandemic and allegations of corruption — not to mention the near-default of Argentina’s state-run driller, YPF SA.

The importance of the job is not lost on the thousands-strong workforce. “We feel the magnitude,” said construction manager José Ibarra, surveying the expanse of desert scrub from behind a pair of sun goggles. “It feels like the whole country is behind us.”

It’s a race against time since June 20 falls early in Argentina’s winter, when gas demand jumps. The government, betting that the pipeline will be finished on schedule, has ordered just 30 liquefied natural gas cargoes for the coming months, 11 fewer than last year. Any delay that forces extra imports would eat into precious government funds, which would be an embarrassing misstep after officials used LNG savings for a sovereign bond buyback.

Meeting the deadline is a huge task by anyone’s measure. “We’re confident, but there are always things that are out of your hands,” said Damián Mindlin, head of Sacde, one of the construction firms building the pipeline.

Export potential

Argentina’s natural gas production reached 140 million cubic metres (4.9 billion cubic feet) a day last winter and the new pipeline would provide an extra 21 million of transport capacity, allowing shale drillers to ramp up operations. Eventually, the logic goes, the country would export to neighbouring Brazil by land and to the rest of the world by sea in the form of LNG cargoes. By comparison, the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico — the world’s most prolific shale formation — pumps about 22 billion cubic feet a day.

Though Argentina doesn’t have any LNG export terminals yet, Texas-based Excelerate Energy and Transportadora de Gas del Sur SA will decide in the next few weeks whether to build a small-scale one. YPF and Malaysia’s Petroliam Nasional Bhd are studying the feasibility of a bigger facility.

As for exports to Brazil, they depend on Argentina luring lenders to finance an extra section of the Néstor Kirchner duct. That’s no sure thing: Argentina’s woes largely keep it locked out of international credit markets, and it’s paying for the first section with tax revenues, including a one-off pandemic wealth tax. Each section would cost about US$2.5 billion, for a total of US$5 billion.

Vaca Muerta’s oil production, meanwhile, is also set for a boost. Oldelval SA, which transports most of the region’s supply, and storage company Oiltanking Ebytem SA are planning to double capacity after the government renewed their operating licences last year.

It’s good timing: With peak oil demand still a way off and US shale production growing more slowly, a window of opportunity has opened for Vaca Muerta since there are few additional supplies beyond OPEC that can come to market soon.

Efficiency gains

Years of efficiency gains in Vaca Muerta mean some crude drillers can break even at as low as US$30 a barrel. That would put them on a par with shale rivals in the US.

“With these pipeline plans, we’ll comfortably reach the goal of one million barrels a day of shale oil by 2030,” said Omar Gutiérrez, the governor of Neuquén, the province with the lion’s share of Vaca Muerta. About half of that could be shipped to international buyers, Gutiérrez said.

The Neuquén Basin was producing a record 373,000 barrels a day at the end of last year, almost two-thirds of all the oil in Argentina. But a decade after its massive oil and gas reserves lured the likes of Chevron Corp. and Shell Plc, output from Vaca Muerta still doesn’t come close to matching supply from the Permian.

Oldelval has already been auctioning off the extra space to shale drillers, some of whom — in a clear sign of the transportation squeeze — have even resorted to taking shale oil to the Atlantic coast in trucks.

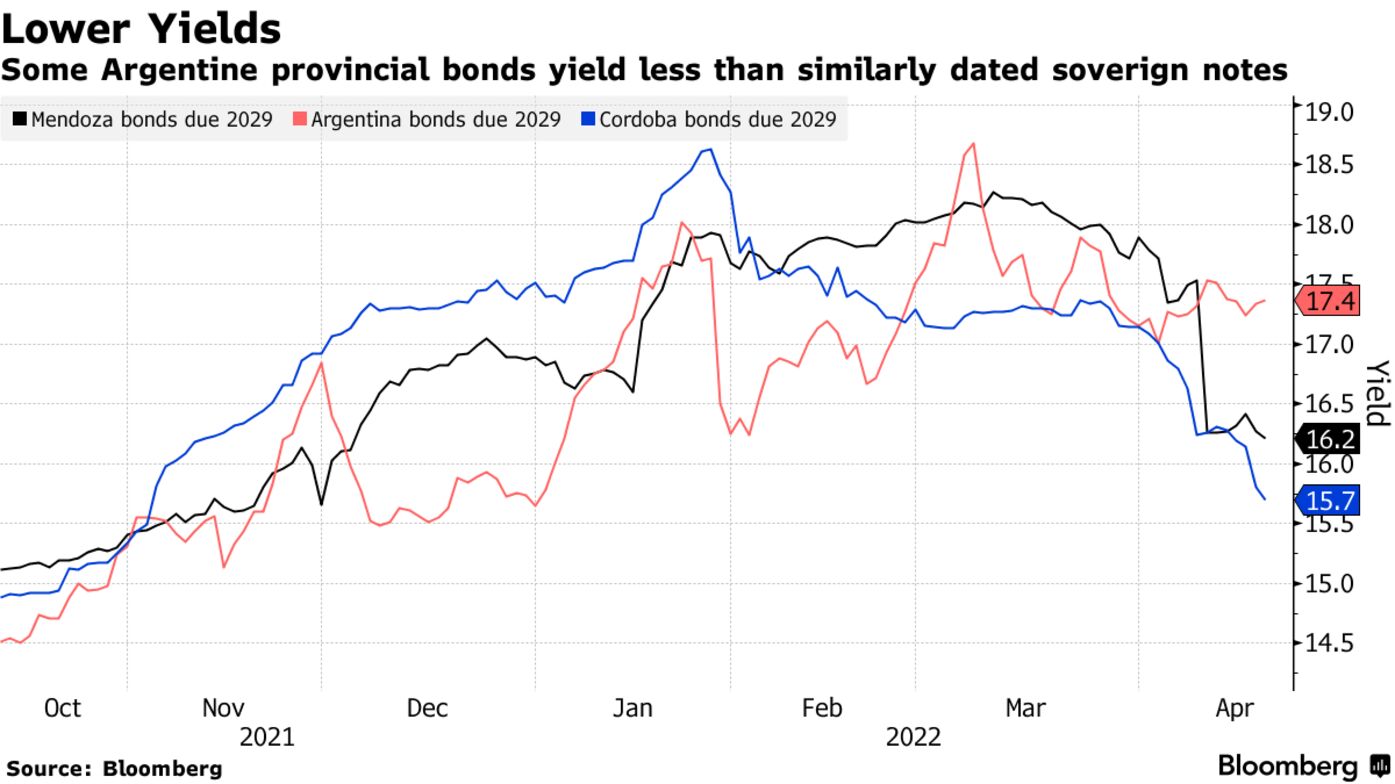

Government incentives are facilitating bond sales to finance pipeline expansions amid Argentina’s lousy credit climate. But intervention is a double-edged sword for drillers.

The government keeps domestic fuel prices artificially low to protect consumers, often hurting producers. Currency controls, designed to defend the peso, make it hard for the country’s drillers to get the US dollars they need to buy equipment or send profits to investors. And local refiners have the right of first refusal to buy oil that might otherwise fetch higher prices overseas, a hurdle to long-term export contracts. Those kinds of measures have been major hurdles to Vaca Muerta’s development.

Still, Miguel Galuccio, chief executive officer of Vista Energy, a top-three crude producer in the shale patch, says this time could be different.

“Progress of pipeline projects is key to attracting more investment and potentially leading Argentina to be a relevant energy exporter,” Galuccio said.

by Jonathan Gilbert, Bloomberg