Politics

Argentina’s Government Faces Midterm Pain Amid Wrecked Economy

By- Argentines vote Sunday in congress election amid 50% inflation

- Unity of ruling coalition at stake on expected seats losses

Argentines cast their ballots Sunday in midterm elections where the ruling coalition stands to lose power in congress to a reinvigorated opposition amid faster inflation and growing economic troubles.

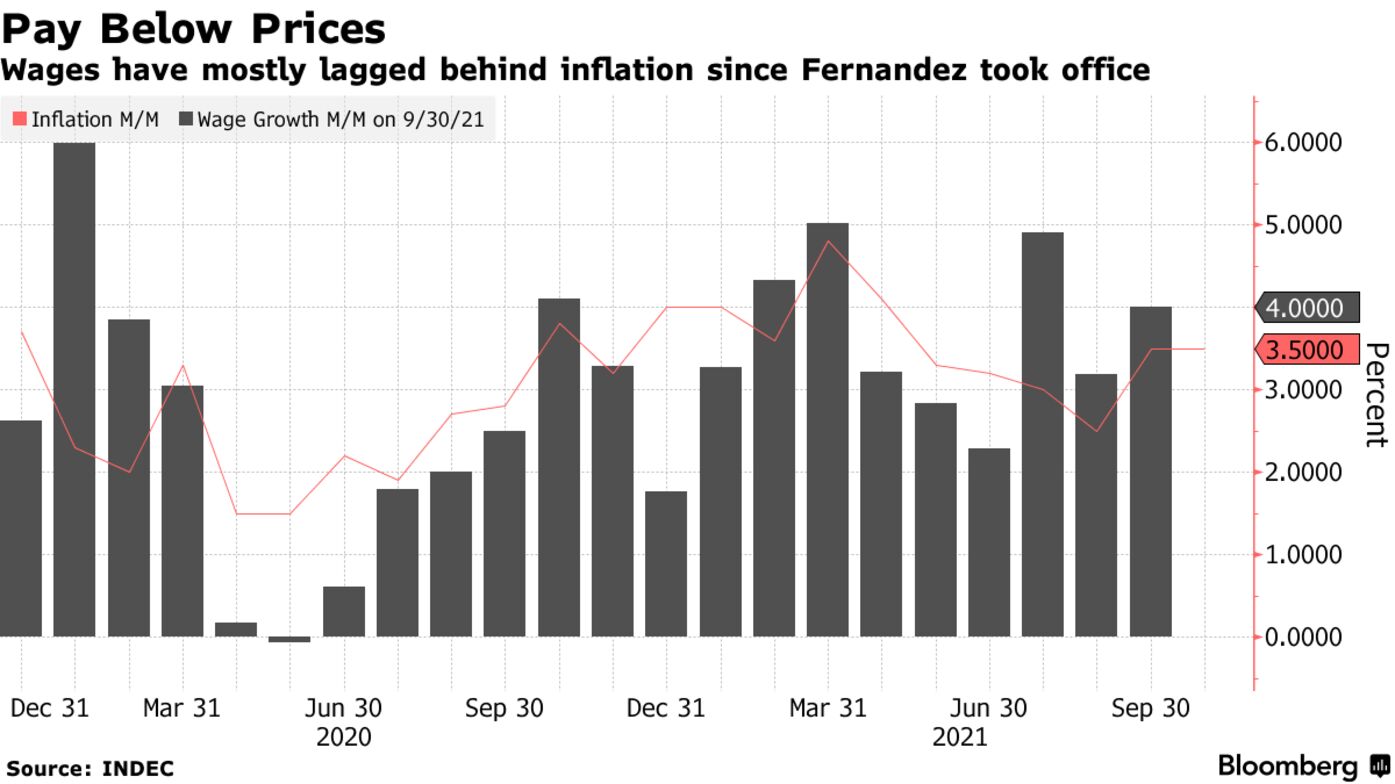

Voters will pick half of the lower house seats and a third of the senate, in an election that will act as a crucial test for the government’s fragile unity. Argentina faces a complex negotiation with the International Monetary Fund over more than $40 billion in loans, with the crisis-prone economy drifting through 50% inflation, 40% poverty and no access to international debt markets.

“Doors are closing in, the problems keep getting bigger, the costs to resolve those problems keep getting bigger and as always nobody wants to pay those costs,” Marina Dal Poggetto, director of Buenos Aires-based consulting firm EcoGo, said. “Incomes are worsening, poverty is rising -- it’s a social time bomb.”

The ruling Peronist coalition, heir of the political movement President Juan Peron founded in the 1940s, lost the majority of races in a September primary vote, exposing a deep political divide between President Alberto Fernandez and the powerful Vice President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who herself governed the nation from 2007 to 2015 with anti-business policies.

If the primary results repeat again on Sunday, the coalition would lose its majority in the senate and the first minority in the lower house, where it controls 47% of lawmakers compared to 45% by the main rival coalition. Voting starts at 8 a.m. local time and results are expected on Sunday night.

On the final campaign rally Thursday night, Fernandez acknowledged some of his government’s shortages.

“The pandemic hasn’t let me in these first two years get things done at the speed or form that I wanted to,” the president said on stage with Kirchner, who didn’t make a speech. “It’s not that we weren’t capable -- the world put us in this situation.”

For the opposition parties, the vote represents an opportunity to signal a more unified, pro-market coalition could return to government in 2023 after then President Mauricio Macri lost a re-election bid two years ago. Additional legislative seats also means they are likely to boost demands for a change toward more business-friendly policies.

Explosive Letter

In the days after the September vote, Kirchner penned an explosive essay criticizing Fernandez, prompting the president to reluctantly fire loyalists from the cabinet and boost his anti-IMF rhetoric in a concession to the coalition’s hard-left groups. Tapping governor Juan Manzur as cabinet chief brought expectations that Peronist regional bosses -- key power brokers in Argentine politics -- would rally behind the government and provide political stability.

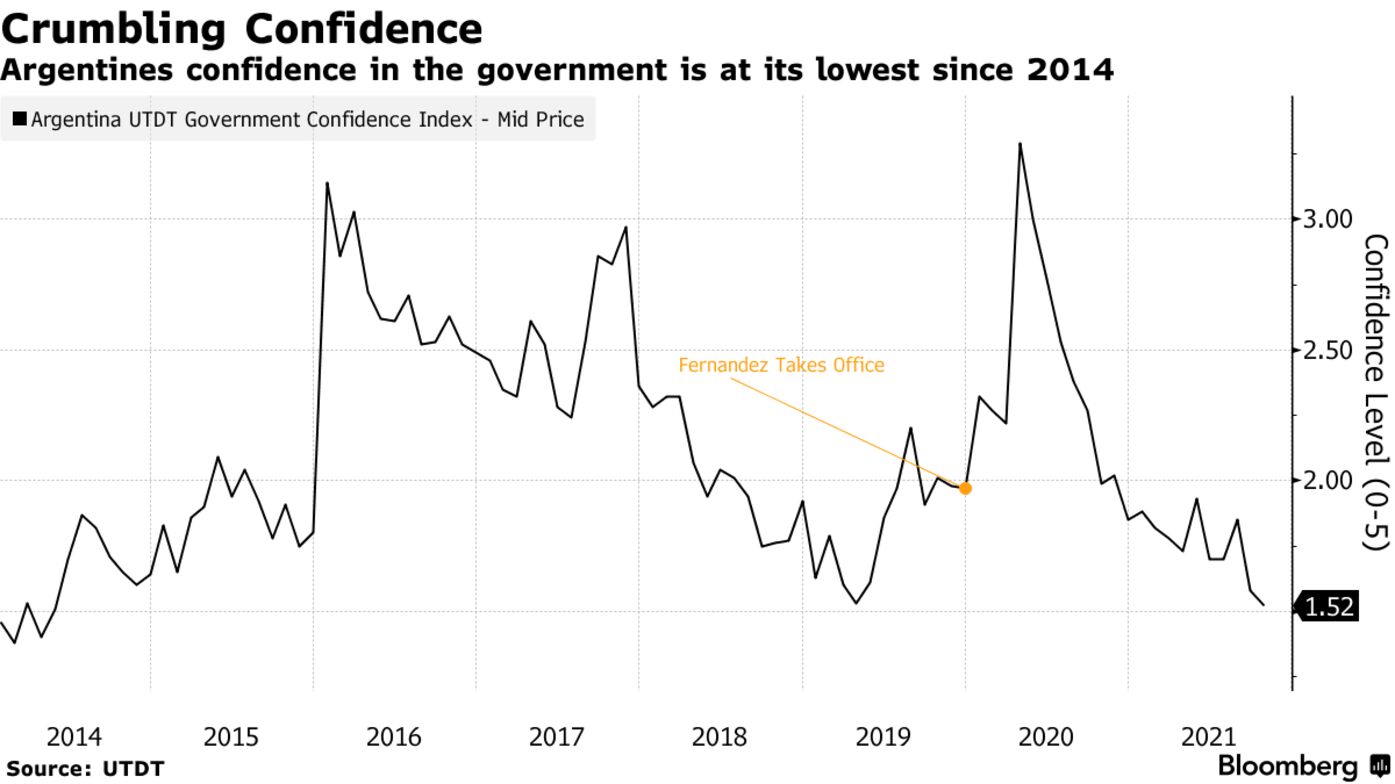

Yet a major shift in strategy hasn’t emerged in the past two months, with faster price gains and social unrest hindering the coalition’s standing. Fernandez was already under fire for a birthday party scandal despite ordering a strict lockdown during the pandemic, causing Argentines’ confidence in the government to plunge to the lowest since 2014.

Those cabinet changes “were more cosmetic than anything else,” Camila Perochena, a professor at Torcuato di Tella University in Buenos Aires, said. “Manzur wasn’t able to achieve the order that he’d hoped to, so more cabinet changes are very likely.”

Worried Investors

Investors also worry the government could reinforce its unorthodox policies, even potentially defaulting on the IMF, if it loses by a wider margin. In October, after failing to reach a deal with businesses, officials decided to freeze prices on over 1,400 household items. That comes on top of byzantine currency restrictions, capital controls, a ban on firing workers and one of the world’s highest inflation rates.

“Investors want the Peronists to lose, but not too badly,” says Edwin Gutierrez, a portfolio manager at Aberdeen Asset Management in London. “If they get blown out, then there’s the danger they could become unpredictable. Nobody knows what Cristina Fernandez will do if she feels cornered.”

Read More: In Argentina, Economists See Policy Continuity in 2022

In campaign mode, Fernandez and his Economy Minister Martin Guzman have lately hardened their rhetoric on the IMF, with the president declaring Argentina “won’t kneel” to the Washington-based institution. Even if Argentina needs a new IMF deal to put the economy back on track after the record bailout given to Macri’s government in 2018 failed to stabilize it, Fernandez is unwilling to commit to the multiyear fiscal effort that such deals usually entail.

Fears are thus growing -- in the government, Washington and Wall Street -- that no deal will be reached between the parts before large payments are due in March after more than one year of low-intensity talks. Not paying the IMF would cut off Argentina from almost all forms of international financing, while it would be a black eye for the institution’s reputation.

In any case, it’s the vice president’s voice that everyone wants to hear after the midterm, including if she still supports Guzman as Argentina’s top negotiator in the IMF talks.

“The big question is, what does Cristina Kirchner want to do?” says Alejandro Catterberg, director of pollster Poliarquia. If the coalition performs worse on Sunday than in the primary, “that’ll influence the decision of whether Kirchner’s base will or won’t support a deal with the IMF.”

— With assistance by Scott Squires, and Ignacio Olivera Dol

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen