Ukraine’s Army Is Underfunded, Outgunned and Not Ready to Stop a Russian Invasion

The Defense Ministry had proposed spending money on pricey waffle towels when basic supplies were more urgently needed.

Ukraine’s military is much stronger and better prepared than 2014, when it couldn’t resist Russia’s annexation of Crimea. But a lack of weapons from the West and underspending at home has left its troops without even the deep stocks of basic supplies they’d need in a high intensity conflict.

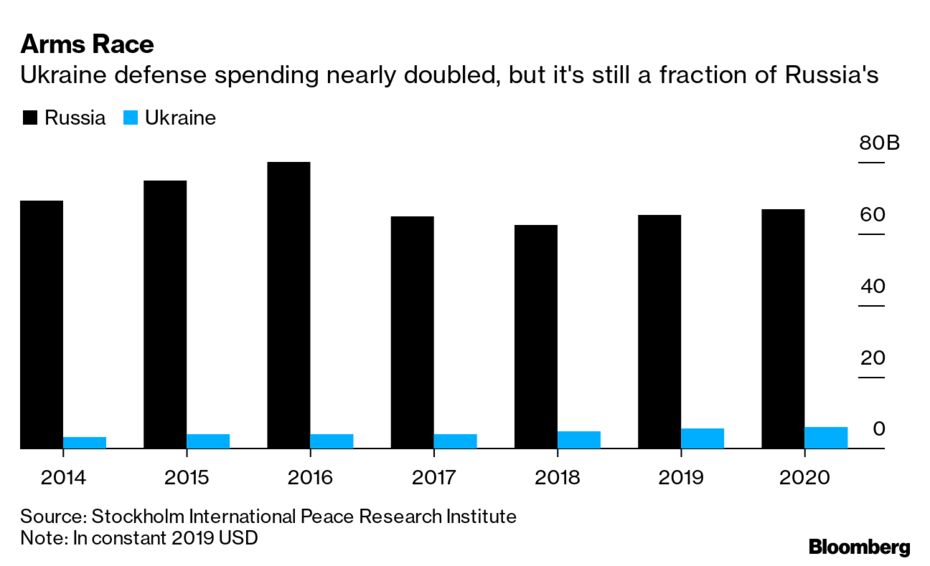

Instead, as fears rise in the U.S. and Europe of a potential invasion by President Vladimir Putin, Ukraine finds its army dwarfed by Russia’s forces and its spending power. The Russian president has sustained his latest troop buildup on the border, saying the North Atlantic Treaty Organization must reduce its presence in the region.

In the event of a war, only a massive influx of sophisticated weaponry from Kyiv’s Western backers could ensure its defense. So far its requests for big ticket items like air and missile defense systems have gone unanswered despite assurances that “NATO stands with Ukraine.”

The U.S. has put together a fresh package including Javelin anti-tank missiles, small arms, medical kits and body armor, sticking to defensive weapons and support for Ukraine’s cyber capabilities in a bid to help Kyiv without giving Putin an excuse for action, people familiar with the discussions said, adding that President Joe Biden has signed off on the plan. National Security Council spokespeople didn’t immediately comment.

At home, meantime, money is short. Some funds collected from taxpayers for defense are spent elsewhere, while waste and corruption still take a toll after years of attempted reform.

Kyiv’s budget for defense procurement was 23 billion hryvnia ($838 million) for 2021, rising to 28 billion hryvnia for 2022. That's a big increase from 2014 but still a rounding error in terms of what the Kremlin has outlaid. Russia spends about 40% of its $60 billion-plus defense budget on procurement, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, twice as much in absolute terms as France, Germany or the U.K., let alone Ukraine.

All wage earners in Ukraine have to pay a special levy, sold as a way to boost defense spending. In 2021 that raised 28.6 billion hryvnia, enough in theory to double arms procurement. Yet the money goes into the general tax fund. A Finance Ministry spokesperson said it was “impossible'” to know whether it was spent on defense, health or other priorities.

When the Defense Ministry came to parliament in December with its shopping list for 2022, news of the Russian troop build-up had long since broken. But the number of bulletproof vests it wanted to buy was just half the amount needed for current troop numbers, let alone the reserves that would be called up should a Russian invasion materialize, according to Serhiy Rakhmanin, an opposition lawmaker and member of the parliamentary committee on National Security, Defense and Intelligence.

Due to a lack of funds, there weren’t enough rifles or helmets on the list either, said Rakhmanin, a former journalist who has been critical as a lawmaker of President Volodymyr Zelenskiy and his government. There was however a request for remarkably pricey waffle towels and Soviet-era radiation detection equipment that’s no longer of obvious utility.

“I had a question: OK, let’s say war starts tomorrow, do you really need this stuff?” Rakhmanin said. The towels and detectors were removed from the list.

The Defense Ministry has pledged to upgrade its procedures, blaming delays in procurement on bureaucracy and promising to reduce classified contracts in order to reduce corruption. Multiple requests for a response to Rakhmanin’s claims did not elicit a comment.

The National Security and Defense Council also said in late December the government will set up an interagency working group to verify the supply of weapons and food to the military over the 2017-2021 period.

Military Buildup on Ukraine Border

Russia has positioned tanks, artillery and air defense at multiple sites

Note: Map shows main units confirmed by satellite imagery

Sources: Janes, OpenStreetMap contributors

The military has nonetheless made strides over the last seven or so years. In 2014 it could put just a fraction of a nominal force of 120,000 troops into combat, with battle tanks mothballed, major air defenses inoperable and just four MiG-29 jets out of a fleet of 46 fit to fly, according to Mykola Bielieskov, a defense analyst at the National Institute for Strategic Studies, a think tank attached to the Ukrainian presidency.

Today, Ukraine is capable of deploying the majority of its 205,000 active troops, together with working, if often vintage, equipment, says Bielieskov. Its Soviet-legacy arms industry has developed new missiles, surveillance drones and radar-guided anti-artillery capabilities.

The problem is the government hasn’t bought enough of even its own new weapons to take on Russia.

“Is Ukraine ready to fight? Yes and no, because Ukraine didn’t start this war,” Hanna Shelest, the Odessa-based editor of Ukraine Analytica, said last month during a U.S. Council on Foreign Relations webcast. She was referring to the conflict with Russian-armed separatists that Ukraine’s military has been fighting in the eastern Donbas region since the annexation of Crimea.

At the same time, Shelest said, the nation’s institutions, military and people are now much better prepared in case Putin decides to escalate.

It remains unclear what Putin’s intentions are, as he simultaneously pursues diplomatic negotiations with Biden and a military buildup. He has repeatedly denied he currently plans to invade.

Read more: Mud Could Help Decide Timing of Any Russia Move Against Ukraine

Russia's large deployment is expensive and difficult to maintain for long. At the same time Putin’s list of diplomatic demands is so expansive they could take months if not years to negotiate, according to Michael Kofman, research program director at CNA, a Virginia-based think tank.

“It is clear by now that the Russians don’t think they will suffer devastating casualties,” he said.

In any operation, Russia could first use its technological advantages to disable the Ukrainian military from afar, obliterating its air force, runways, air defenses, munitions dumps and command and control systems in a barrage for which Ukraine would have little or no response, according to Kofman and others.

Ukrainian troops might have little chance to make use of their vaunted U.S. Javelin anti-tank weapons and armed drones recently acquired from NATO member Turkey, before a punitive settlement was imposed.

“Ukrainians know how to fight, but they do not have the equipment, especially for deep operations,” said Bielieskov. “The Russians have Iskander (ballistic) missiles, electronic warfare, latest generation aircraft and all these things.”

Visiting Washington in November, Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov said he’d asked for the high-end equipment Ukraine would need to start redressing the imbalance. Yet U.S. missile and air-defense systems would be difficult to quickly transport and integrate for use in Ukraine, even if a political decision was taken for America to become so deeply involved in a potential conflict with Russia.

The U.S. says it has delivered $2.5 billion in military aid to Ukraine since 2014, but that was designed to contain militants in eastern Ukraine, rather than a full Russian invasion.

Other NATO countries have also provided aid and training, but Zelenskiy has accused Germany of blocking the alliance as a whole from providing more arms. Germany and the Netherlands say so long as there is a threat of conflict with Russia, NATO should not give Ukraine lethal weapons, Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration Olha Stefanishyna told Interfax-Ukraine Tuesday.

Estonia plans to provide howitzers and Javelin missiles, primarily for anti-tank defense, the ERR news service reported last week. To do so it would need permission from the U.S., Germany and Finland, where the equipment originated. The Biden administration is in favor of the idea in principle, according to one person familiar with the administration’s thinking.

Additional shoulder-fired anti-aircraft weapons would be a more pragmatic ask than Patriot batteries, according to Bielieskov. These require little training and would allow troops to counter Russian helicopter gunships and force its attack jets to fly at higher altitudes, reducing their effectiveness and helping Ukrainian forces survive bombardments.

But for Glen Grant, a retired British artillery officer and ex-adviser to Ukraine’s parliament on military reform, officials need to focus on basic supplies — building the missing reserves of food, ammunition and light transport.

“Numbers don’t count for much, it is the ability to put the troops in the right place with the right equipment and the right moment that’s vital,” said Grant, now senior expert at Latvia’s Baltic Security Foundation. “The burn rate in a major war is huge, it will dwarf anything that happened in 2014.”

— With assistance by Alberto Nardelli, and Jennifer Jacobs

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen